Analyzing plants with a CT scanner may seem like a curious idea, but the Fraunhofer Development Center X-ray Technology EZRT, a research division of the Fraunhofer-Institute for Integrated Circuits IIS and Dutch company PhenoKey were confident it could work. Now, their joint development project has produced a robust CT scanner specifically designed for use in plant breeding. We talked to department head Dr. Stefan Gerth of the Fraunhofer Development Center X-ray Technology EZRT and PhenoKey managing director Bas van Eerdt to find out how CT data can make life easier for breeders – and why e-resourcing is such an important part of the puzzle.

Plant breeding has been practiced for centuries. By crossing male and female plants that have certain desirable characteristics, plant breeders aim to produce progeny that offer higher yields or fruits with improved flavor. So what additional benefits can breeders gain from the system you teamed up to develop?

Stefan Gerth: It’s important to understand that you need huge quantities of plants for breeding and research. Scientists typically sow hundreds of seeds in crossbreeding experiments in the hope that some of the progeny will have advantageous traits. Experienced breeders can identify the most promising candidates by sight from among thousands of cross-bred plants, which is how they determine which ones should enter the next stage of the process. This assessment and selection of physical traits is what we call phenotyping. The problem in the past was that you couldn’t examine the underground part of a plant – like a potato, for example – without pulling it out of the ground and destroying it. But now we’ve developed a computer tomography method that allows us to x-ray the part of a plant that grows underground. The resulting CT scan has an extremely high resolution and a size of around 40 gigabytes, which is similar to the storage capacity of a basic smartphone. It shows every last detail of the plant.

What are the benefits of such a detailed scan?

Stefan Gerth: We can extract a huge amount of information from the scan data, such as the size of a potato tuber or the density of a plant’s root system. This can tell us whether the plant is getting enough nutrients and water. What’s more, the depth of the root system plays an important role in determining whether a plant can survive in dry soils. We never used to have access to this kind of in-depth information because the only way to examine the tubers was to pull the plant out of the ground, which destroyed the root system. But now we can even see how a plant is evolving over time by scanning it at regular intervals.

Mr. van Eerdt, you’re using Fraunhofer technology to build fully automated phenotyping systems. Who are your customers?

Bas van Eerdt: Our customers include scientific laboratories that conduct basic research into plant traits and how plants interact with their environment. Climate change is making it more important than ever to understand how plants respond to drought and heat stress, and scientists also hope to discover ways to boost plants’ stress tolerance. Our customers also include some of the world’s big seed breeding companies, which have tens of thousands of plants in their greenhouses that need to be assessed.

And does automation hold the key to tackling those kinds of quantities?

Bas van Eerdt: The first thing to understand is that our technology isn’t designed to replace plant breeders and assessors. We’re simply giving them a new tool that they can use to quickly and objectively evaluate large numbers of plants in a fully digital process. Ultimately, the purpose of the system is to help breeders identify the best plants.

A 40 GB, fully digital scan sounds huge! How can customers deal with all that data?

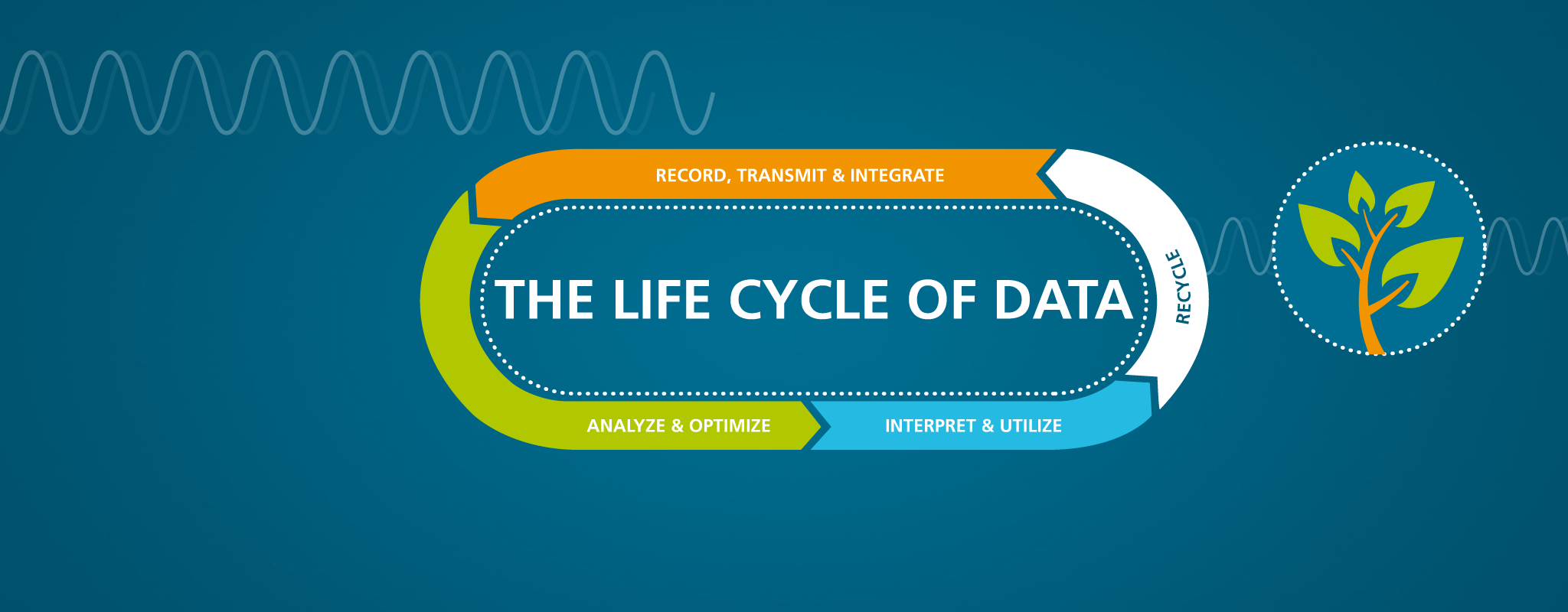

Stefan Gerth: The secret lies in e-resourcing – that’s what allows companies to put these powerful, sophisticated and data-intensive CT scanners to effective practical use. Our customers simply wouldn’t be able to operate these systems without e-resourcing, and they wouldn’t have access to the unique and comprehensive information on plants that these systems generate.

With this new system, we can quickly assemble a wealth of previously unavailable data on things such as the number and thickness of potato tubers or the density of the root system. In the case of peas or peanuts, it allows us to inspect the quality of the seeds in the pods from the outside. We’ve developed a belt conveyor system that transports large numbers of plants through the CT scanner in a short timeframe. Bas has a clear understanding of what breeders need, and we know just how much useful information can be extracted from data. Our discussions have already produced all sorts of great ideas. Ever since we first met at a scientific conference a few years ago, we’ve been working together on ways to develop the concept of CT phenotyping into a complete, turnkey system. The system can provide breeders with the parameters they routinely need for phenotyping, but it also offers lots more data that hasn’t even been exploited yet.

Who else can benefit from this information and your system?

Bas van Eerdt: There are definite benefits for the manufacturers of crop protection products, including biologicals. CT scans give them a more objective and accurate method of determining how plants respond to the administration of active ingredients. It’s also conceivable that the new insights we’re now getting into plants will lead to better methods of cultivation in agriculture, which may help us respond better to climate change. And – who knows? – perhaps in a few years from now, we might have a CT scanner that’s robust enough to use not only in greenhouses but even out in the fields!